Economist Nouriel Roubini believes the world economy is lurching toward an unprecedented confluence of economic, financial, and debt crises, following the explosion of deficits, borrowing, and leverage in recent decades.

By* Lorimer Wilson, Managing Editor of munKNEE.com – Your KEY to Making Money. Here’s why.

In his latest commentary, titled ‘The Unavoidable Crash’, Roubini writes: After years of ultra-loose fiscal, monetary, and credit policies and the onset of major negative supply shocks, stagflationary pressures are now putting the squeeze on a massive mountain of public- and private-sector debt. The mother of all economic crises looms, and there will be little that policymakers can do about it.

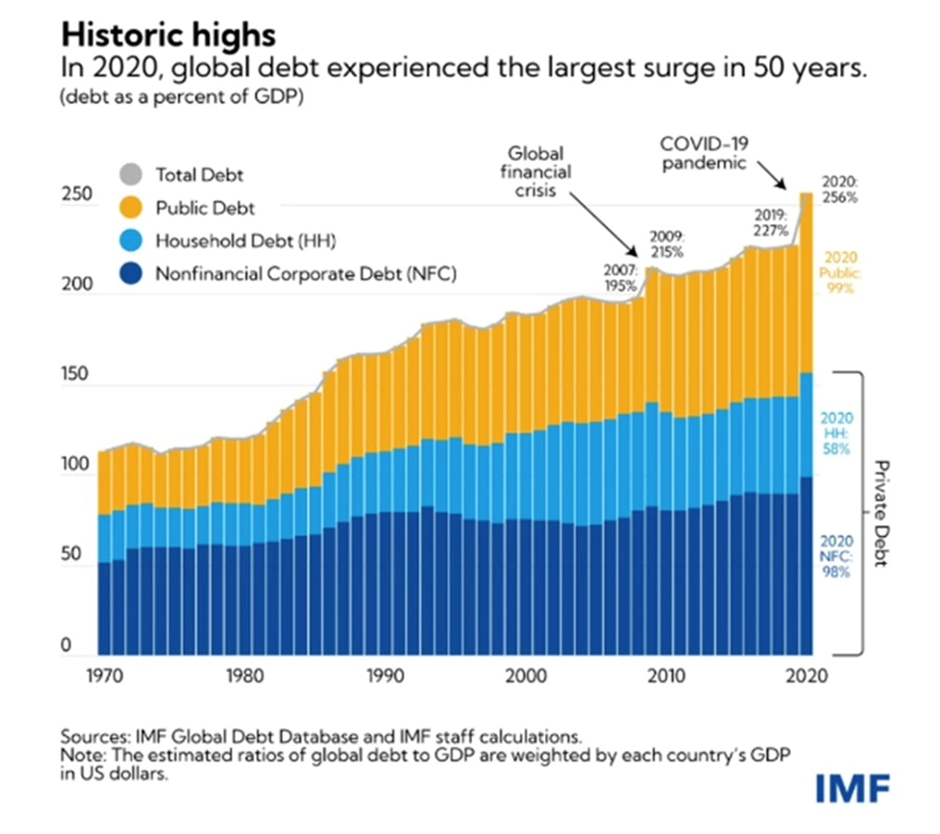

Central to his thesis is the mountain of private and public debt that has been accumulating. Private debt includes corporations and households (mortgages, credit cards, car loans, etc.) while public debt comprises government bonds and other formal liabilities, as well as implicit debts such as pay-as-you-go pension schemes.

Globally, total private- and public-sector debt as a share of GDP rose from 200% in 1999 to 350% in 2021. The ratio is now 420% across advanced economies, and 330% in China. In the United States, it is 420%, which is higher than during the Great Depression and after World War II.

For years, many at-risk borrowers were propped up by ultra-low interest rates, which kept their debt-servicing costs manageable but now, inflation has ended what Roubini calls “the financial Dawn of the Dead”. Central banks, forced to raise interest rates to deal with inflation, have sharply increased debt-servicing costs (higher interest):

For many, this represents a triple whammy, because inflation is also eroding real household income and reducing the value of household assets, such as homes and stocks. The same goes for fragile and over-leveraged corporations, financial institutions, and governments: they face sharply rising borrowing costs, falling incomes and revenues, and declining asset values all at the same time.

The next part of Roubini’s argument harkens back to an earlier article he wrote, titled ‘The long forecast stagflationary debt crisis of the world has begun’.

According to Roubini, global debt, when combined with the coming stagflation, sets up a “stagflationary debt crisis” (stagflation = high inflation + low growth). What would this look like?

The first thing to understand, is this stagflationary period differs from that of the late 1970s/ early 1980s, due to the much higher debt levels. read: A stagflationary debt crisis looms.

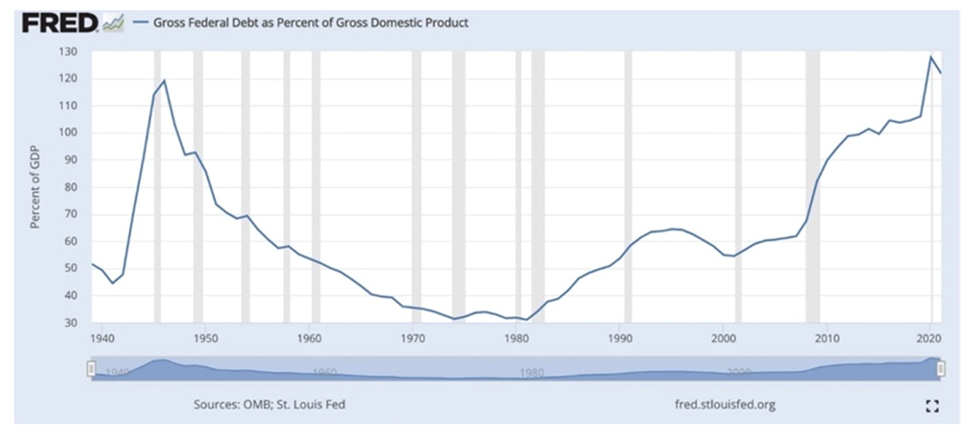

According to the FRED chart below, the US debt to GDP ratio in the ‘70s was around 35%. Today it is three and a half times higher, at 125% and this severely limits how much and how quickly the Fed can raise interest rates, due to the amount of interest that the federal government will be forced to pay on its debt.

US debt to GDP ratio

US debt to GDP ratio

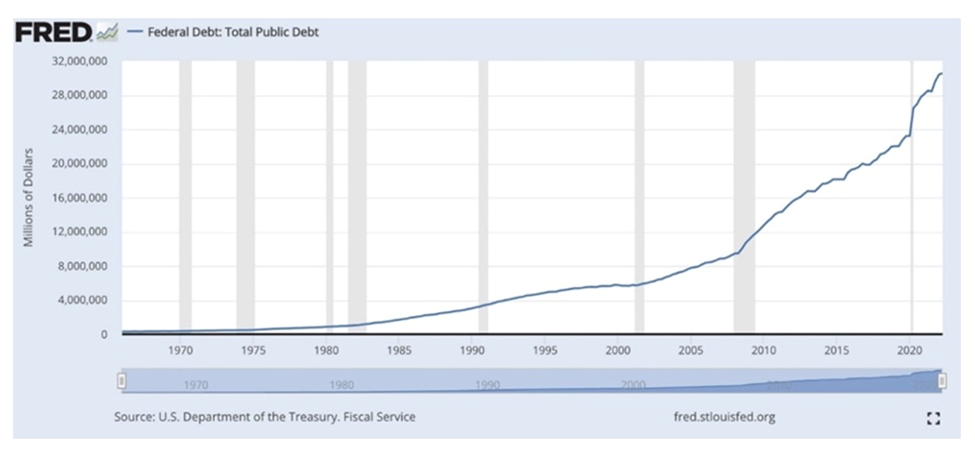

Total public debt

Total public debt

During 2021, before interest rates began rising, the federal government paid $392 billion in interest on $21.7 trillion of average debt outstanding, @ an average interest rate of 1.8%. If the Fed raises the Federal Funds Rate to 4.6%, interest costs would hit $1.028 trillion — more than 2021’s entire military budget of $801 billion!

The national debt has grown substantially under the watch of Presidents Obama, Trump and Biden. Foreign wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been money pits, and domestic crises required huge government stimulus packages and bailouts, such as the 2007-09 financial crisis and the covid-19 pandemic in 2020-22.

Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. That increase is reflected in the annual budget deficit, which keeps getting added to the national debt, now sitting at a shocking $31.3 trillion.

Now let’s bring in what Roubini says about the stagflationary debt crisis. First, he argues that debt ratios in advanced economies and most emerging markets were much lower in the 1970s, compared to today.

Conversely, during the financial crisis, high private and public debt ratios caused a severe debt crisis, exemplified by the housing bubble bursting. The ensuing recession led to low inflation/ deflation (falling prices), and there was a shock to aggregate demand. This time, however, we can’t simply cut interest rates to stimulate demand. Today, the risks are on the supply side, such as the Ukraine war’s impact on commodity prices (fertilizer, food, diesel, metals) China’s zero-covid policy, and a series of prolonged droughts.

According to Roubini, the economist who predicted the 2008 market meltdown,

Unlike in the 2008 financial crisis and the early months of COVID-19, simply bailing out private and public agents with loose macro policies would pour more gasoline on the inflationary fire. That means there will be a hard landing – a deep, protracted recession – on top of a severe financial crisis…

With governments unwilling to raise taxes or cut spending to reduce their deficits, central-bank deficit monetization will once again be seen as the path of least resistance but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time. Once the inflation genie gets out of the bottle – which is what will happen when central banks abandon the fight in the face of the looming economic and financial crash – nominal and real borrowing costs will surge. The mother of all stagflationary debt crises can be postponed, not avoided.

Targeting the wrong inflation

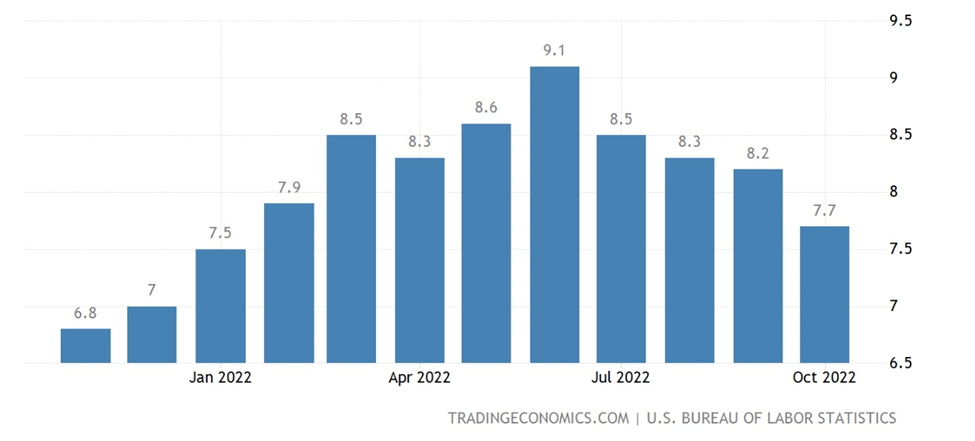

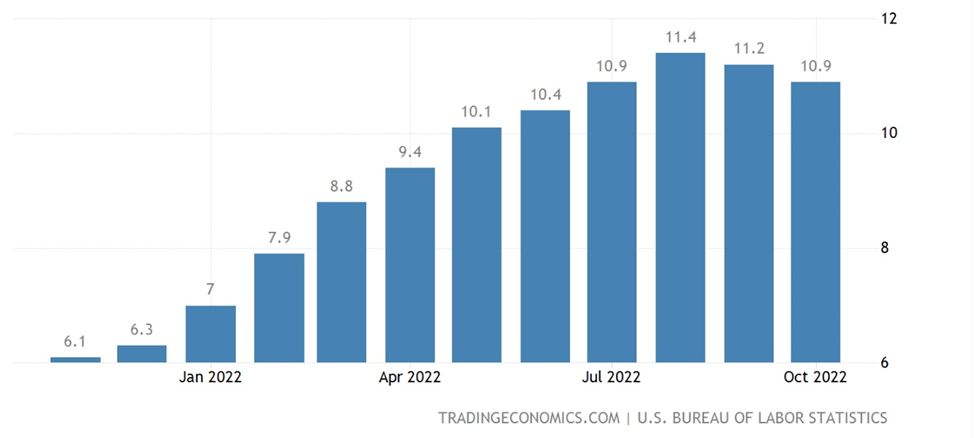

Another key point, that ties into what Roubini is saying, is the fact that the Federal Reserve is targeting the wrong inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is currently 7.7%. This is the number most quoted in the financial press; it is the official inflation rate. The CPI includes food, energy and rent increases.

US inflation (CPI). Source: Trading Economics

US inflation (CPI). Source: Trading Economics

In contrast the Fed’s go-to inflation gauge, core PCE, under-weights rent and over-weights health care. It also strips out two of the most vital categories of household spending, food and energy/ gasoline.

According to Moody’s Analytics’ analysis of October 2022 inflation data, via CNBC, the average American household is spending $433 more a month to buy the same goods and services it did a year ago.

Among the most dramatic price increases, food at work and school rose 95.2%, eggs were up 45%, butter and margarine climbed 33.2%, and public transportation was 28.1% more expensive. These are all “non-discretionary” expenditure items.

While October’s core CPI was down 0.3% compared to 6.6% in September, the so-called necessities of life — shelter, food and energy — continue to climb. Year over year, shelter prices are up 6.9%, food prices gained 10.9%, gasoline prices rose 17.6%, and staples such as eggs (+43%), bread (+14.8%) and milk (+14%) remain elevated, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Surely for the broader CPI to fall substantially, food and energy costs must decline; I have my doubts whether this will happen anytime soon.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, food prices in 2023 are predicted to rise between 3 and 4%. Within this category, food at home prices are forecast to rise 2.5-3.5%, and food away from home is expected to go up 4-5%.

US food inflation. Source: Trading Economics

US food inflation. Source: Trading Economics

As for energy prices dropping, they probably won’t, at least not for the foreseeable future. When the OPEC+ group of countries meets on Dec. 4, they are expected to stick to their current output target, two sources told Reuters on Friday. The 13-member crude oil cartel plus 10 other oil-exporting nations, including Russia, in October agreed to cut their collective oil production by 2 million barrels a day.

WTI crude futures have come down considerably from their one-year pinnacle of $119.78, on March 8, but they remain high by historical standards. Ditto for US natural gas futures and US retail gasoline.

WTI crude futures. Source: Trading Economics

WTI crude futures. Source: Trading Economics

US natural gas futures. Source: Trading Economics

US natural gas futures. Source: Trading Economics

US retail gas for the week of Nov. 28. Source: YCharts

US retail gas for the week of Nov. 28. Source: YCharts

Conclusion

If Nouriel Roubini is right about “the mother of all economic crises” heading our way, and we are correct about inflation not coming down, investors would be wise to adjust their portfolios accordingly.

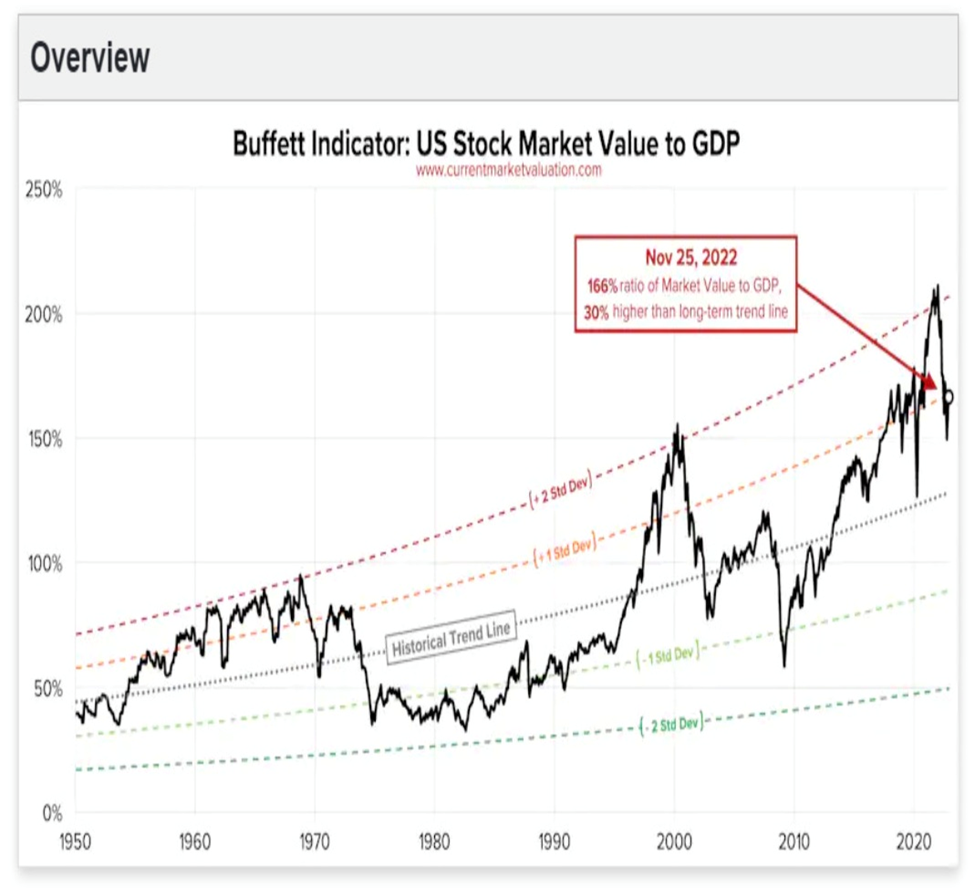

For one thing, the stock market is unlikely to be a growth vehicle.

In a recent letter to investors, Mark Spiegel of Stanphyl Capital said he believes the major indexes, though not all individual stocks, have considerably more downside — “the inevitable hangover from the biggest asset bubble in US history.”

Spiegel via Quoth the Raven (Zero Hedge) also observes that the US stock market’s valuation as a percentage of GDP (the “Buffett Indicator”) is very high, and thus valuations have a long way to go before reaching “normalcy”. The indicator is currently sitting at 166%, 30% higher than the long-term trend line.

As importantly, Spiegel predicts commodities “will have a brand new tailwind in 2023,” thanks to the eventual end of China’s zero-covid policy, its November reversal of bailing out its real estate industry, combined with the end of President Biden’s SPR (Strategic Petroleum Reserve) drawdowns.

The commodities bull market is just getting started

Longer terms, he believes the “war on fossil fuel”, expensive “onshoring”, fewer available workers and perpetual government deficits will make a new 4% baseline inflation likely — double the Fed’s current 2% target.

This shows we’re not alone in thinking that the Fed has to bump up its inflation expectations to fit economic reality, given that price increases are certain to continue into next year and likely beyond.

Spiegel also agrees with Roubini in his assessment of how interest rate increases will play out with US government interest payments on its monstrous debt, writing:

Meanwhile, interest costs on the Federal debt are already set to grow massively. Does anyone seriously think this Fed has the stomach to face the political firestorm of Congress having to slash Medicare, the defense budget, etc. in order to pay the even higher interest cost that would be created by upping those rates to a level commensurate with crushing even just 4% inflation? [let alone the current 7.7% – Rick]

Powell doesn’t have the guts for that, nor does anyone else in Washington; thus, this Fed will likely be behind the inflation curve for at least a decade. And that’s why we remain long gold.”

Few analysts seem to recognize the direct link between debt, looming deficits and inflation. Inflation is the fourth horseman of an economic apocalypse, accompanying stagnation, unemployment and financial chaos. The size of the US government’s debt — currently $31.3T — and unsustainable future deficits, puts us in an unfamiliar danger zone.

Raising interest rates won’t work, because the current inflation is supply-oriented not demand-driven.

The crisis threatens to envelope both the developed economies and the emerging markets. Developing-world economies that borrowed heavily in dollars when interest rates were low, are now facing a huge surge in refinancing costs. About 60% of the poorest countries are already in, or at high risk of, debt distress.

Gold historically performs best when government deficits are large and/ or growing. It appears all but certain the world economy will enter a recession within the next six to 12 months. The warnings are written in the inverted yield curve (an extremely reliable recession indicator), stagnant US manufacturing data, and a return to high debt levels among US and Canadian consumers, post-pandemic. The latter is a concern because it ups the risk of bankruptcies, delinquencies and forced stock selling, amid higher interest rates.

Gold does well during stagflationary episodes. Gold is also a traditional inflation hedge, and while high inflation hasn’t yet resulted in a flight to gold, I believe it will happen when there is a shift from monetary tightening to easing as a result of poor US economic performance and/or the widely anticipated recession. The latter will almost certainly crush the dollar, bringing about higher commodity prices.

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money