I think the Chinese are devaluing the yuan in slow motion but when they  realize that the shadow banking system will tighten credit at the worst possible time – just when the PBOC is actively fighting such tighter credit conditions – they are likely to devalue the yuan by a much larger and less orderly amount.

realize that the shadow banking system will tighten credit at the worst possible time – just when the PBOC is actively fighting such tighter credit conditions – they are likely to devalue the yuan by a much larger and less orderly amount.

The comments above and below are excerpts from an article by Ivan Martchev (Navellier.com) which may have been enhanced – edited ([ ]) and abridged (…) – by munKNEE.com (Your Key to Making Money!)

to provide you with a faster & easier read. Register to receive our bi-weekly Market Intelligence Report newsletter (see sample here , sign up in top right hand corner.)

The well-known Chinese curse – “May you live in interesting times” – is playing before our very eyes with the Chinese yuan cents away from the 6.82 mark, where it got “pegged” to help Chinese companies during the Great Financial Crisis in 2008.

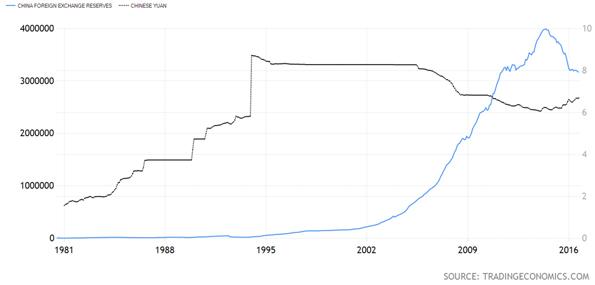

The Chinese started a revaluation cycle back in 2005 to appease the U.S. for their trade surplus as well as a massive U.S. dollar reserve accumulation. The U.S. position was that if the Chinese were to let the yuan float and appreciate, the trade balance would correct itself. The Chinese initially revalued the yuan from 8.28 all the way to 6.82, but were forced to stop at that level as they realized in mid-2008 that Wall Street’s problems were likely to result in a much bigger problem for the world economy.

In some respects, the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 contributed to the present problems in the Chinese economy due to the practice of “forced lending” that was deployed as a response. Since the Chinese government controls the banking sector to a large degree, they simply mandated that banks raise their lending quotas as it became clear that demand for China’s exports was falling in late 2008 and early 2009.

Economics 101 teaches that forced lending does not work. It does help economic growth, but it usually results in more losses down the road. When the Chinese authorities tried to rein in lending, it was already too late – the now infamous shadow banking system had taken over. If the Chinese regulators tried to tighten, Chinese corporate borrowers would go to unregulated lenders, where such curbs were non-existent. By some estimates, unregulated shadow banking lending in just five years has grown to be at least as large as the Chinese economy, which is on track to reach $11.6 trillion at the end of 2016.

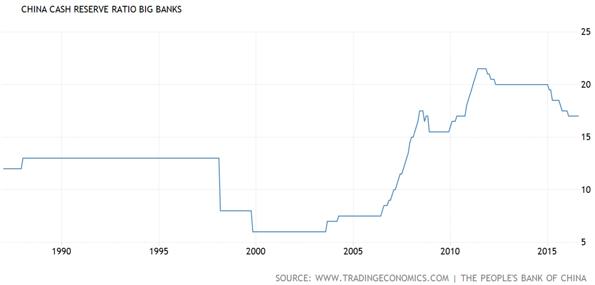

While the Chinese have used reserve requirements at major banks a lot more aggressively than other central banks – tripling the reserve requirements at banks between 2004 and 2012 – they have been lowering them since 2015, affecting the credit multiplier in the Chinese financial system. However, I think the system itself may have gotten away from the Chinese central bank to the point where such monetarist maneuvers like reserve ratio cuts (that were used previously) may no longer work as well.

The reason why reserve ratio cuts may not work well this time is that the unregulated shadow banking system may be responsible for at least 25% of all loans in the economy. Tightening lending standards does not work with unregulated lending and neither does loosening them. The shadow bankers loosen and tighten credit standards on their own, thus overheating the economy when it’s least desirable or pushing it harder down the slippery slope. In effect, unregulated lending loosens the grip of the Peoples Bank of China (PBOC) over the Chinese financial system, which is something the Chinese are wary of.

I think the Chinese are devaluing the yuan in slow motion but when they realize that the shadow banking system will tighten credit at the worst possible time – just when the PBOC is actively fighting such tighter credit conditions – they are likely to devalue the yuan by a much larger and less orderly amount.

The last time Beijing resorted to such a hard devaluation was on Christmas Day in 1993. For all practical purposes, the devaluation took effect at the start of 1994. I think the PBOC wanted to use the holidays to give people time to think things over and ponder what a 34% cheaper yuan meant for their businesses.

While I do not know if a 34% devaluation is coming this time, I do think a “hard” devaluation to the tune of 20% to 40% is coming in the next one or two years. The magnitude of such a hard devaluation will depend on how much the Chinese economy will deteriorate because of its epic credit bubble and at what point in this deterioration process the PBOC decides to act.

The Chinese situation today can easily be compared to the Roaring Twenties, the decade before the Great Depression in the U.S. There was rapid growth in unregulated credit similar to the rapid growth in shadow banking in China today. The Great Depression was exacerbated by the raising of tariffs and the tightening of monetary policy, as well as bank failures in the U.S. and in Europe, so in that regard China does not have to go into a depression if there are no policy errors. It may just be a hard landing or nasty recession.

A hard yuan devaluation acts as an adrenaline shot into the heart of the Chinese economy as it bypasses the shadow banking system. This is why I think it is coming sooner or later. An acceleration in capital outflows – which had calmed down in 2016 – is a good sign that things in China are deteriorating again. Such accelerating capital outflows would mean the chances for a hard devaluation are increasing…

Editor’s Note: No need to “surf the net” looking for the most informative financial articles available. My Facebook page has the BEST financial articles on the internet – bar none! Check it out. I guarantee you will not be disappointed – and don’t forget to “like” or “love” those articles of particular interest to you. I need the feedback.

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money