Based on commonly held perspectives among economists and commentators in the financial media one would think that inflation was something vital to the proper functioning of our economy. Long forgotten, [however, is that]…inflation was seen in the 1970s and 1980s as enemy #1 of the U.S. economy. In this article we discuss the motives and incentives driving the current passion for inflation.

one would think that inflation was something vital to the proper functioning of our economy. Long forgotten, [however, is that]…inflation was seen in the 1970s and 1980s as enemy #1 of the U.S. economy. In this article we discuss the motives and incentives driving the current passion for inflation.

The comments above and below are excerpts from an article by Michael Lebowitz (720Global.com) which may have been enhanced – edited ([ ]) and abridged (…) – by munKNEE.com (Your Key to Making Money!)

to provide you with a faster & easier read. Register to receive our bi-weekly Market Intelligence Report newsletter (see sample here , sign up in top right hand corner.)

Perspective

The first step toward understanding why the Fed and most of the world’s leading economists desire inflation and abhor deflation begins with their economic perspective. Many contemporary economists subscribe to a branch of economics called Keynesianism, a school of thought based on the economic theories of Lord John Maynard Keynes.

While Keynes had many theories, one of his core concepts focused on the overwhelming importance of demand — consumer, corporate and government — to drive economic activity, however, they tend to overlook the dire situation that prompted the birth of these theories…Keynes published his book, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” in 1936 with Europe heading into the maw of war. Defeating fascism was dependent on both military and economic victory. Keynes’ ideas afforded unique new insights into a way European governments could temporarily stimulate demand and run deficits aimed at rebuilding the economy of an entire continent. Keynes’ policies were indeed successful and provided much-needed social stability in the years following World War II…

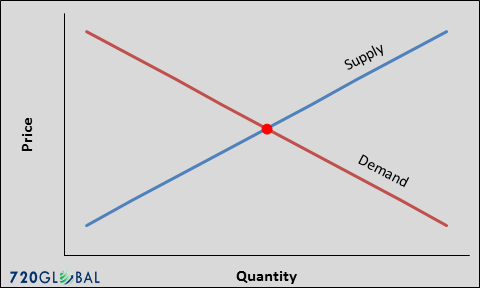

The basic supply/demand curve, as shown below, illustrates the concept that the interaction between supply and demand affects the price, quantity produced and the demand of any item. The intersection of the supply and demand curves is thought to be the optimal pricing point, or the equilibrium price at which quantity supplied is equal to the quantity demanded.

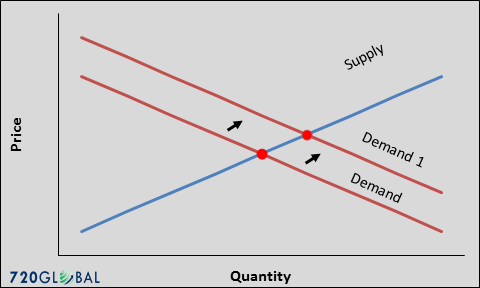

If demand increases, represented as a parallel shift upwards and to the right of the demand curve, and the supply produced of a good does not change to meet the new demand, the price is expected to increase as shown below. Conversely, if the supply were to increase while demand stayed constant, the supply curve would shift down and to the right and prices would be expected to decrease.

Modern economic theories and models presuppose that stimulating the consumption of goods and services is paramount to generating economic activity, and thus many policy setters and legislators lose focus of the supply side of the equation. Taking it a step further, if the supply curve is less important than demand, and greater demand results in higher prices, then price increases or inflation must be a strong signal that demand is rising. Therefore, demand-side theories continuously argue that inflation is proof positive of robust economic activity.

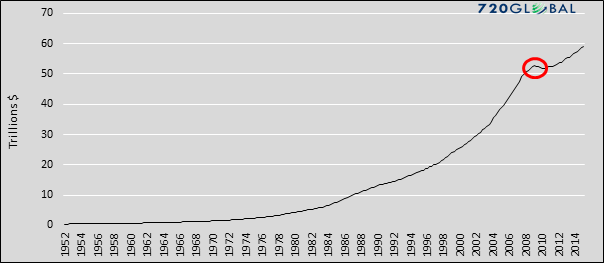

Debt is another reason economists desire inflation. Consumer, corporate and government debt has become the primary emphasis behind most discussions on economic growth. To entice borrowers to take on ever-increasing amounts of debt and therefore stimulate consumption, policy must constantly encourage additional borrowing and help debtors find cheaper ways to service existing debt. As a point of context, the great financial crisis of 2008 offers a textbook lesson on what occurred when, for a brief period, credit did not expand.

Total Credit Outstanding

Data Courtesy: Federal Reserve Z1

Persistent inflation, like low interest rates, has become a tool policy-makers use to minimize the burden of debt. As a simple example, assume a household earns $50,000 a year and takes on a $500,000 mortgage. Servicing such a debt will dramatically reduce the household’s appetite to consume and their capacity to take on additional debt. Inflation, however, can change their situation. If the value of the house appreciates 10% per year, then in five years the house would have increased in value to over $800,000, rewarding our borrower with over $300,000 in equity. Even though the household’s income did not increase, the presence of additional equity in the house allows the household to borrow more and increase consumption.

The Rest of the Story

By narrowly focusing on consumption, economists have lost sight of production. Such disregard for the supply curve is proving to be a costly error.

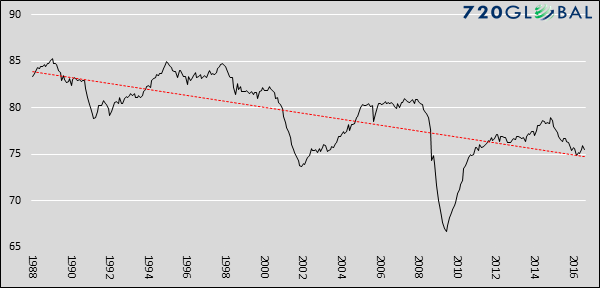

As monetary policy increasingly encouraged debt-financed consumption, corporations responded by expanding their capacity and operations to keep up with the policy-induced demand for their goods. Both the demand and supply curves shifted in unison, reflecting greater demand and production capacity. Unfortunately, over time, the consumers’ ability to take on additional debt has diminished and the demand curve shifted back. The supply curve, however, is less flexible, as corporations cannot easily reduce their production capacity. Attesting to this overbuild is capacity utilization which, as graphed below, is trending lower and stands at a level that has been indicative of recessions in prior cycles.

Capacity Utilization

Data Courtesy: St. Louis Federal Reserve (NASDAQ:FRED)

In response to weaker demand, corporations downsized employment, outsourced production and limited wage increases. Partially as a result of their actions, the labor participation rate lingers at 38-year lows and real median wages are at levels comparable to 1998. Corporations created a negative economic feedback loop as their employees are also consumers of their products.

Another unfortunate consequence of weaker demand is that instead of investing some profits towards productive activities, a majority of corporate cash flows have been diverted to shareholders to engineer better financial ratios and earnings per share to help compensate for weakening sales. The results may be optically appealing and supportive of equity market valuations in the short term, but these decisions are decidedly not constructive for the long-term health of the corporations and the economy.

The bottom line is that disregard for production-oriented aspects of the economy (the supply side) and myopic over-emphasis on debt-financed consumption (the demand side) naturally limited potential corporate and national economic growth.

Summary

After all of the heroics by former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker to arrest inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s we have come full circle. Inflation is now a supposed sign of economic virtue and progress. When practically required as a means to decrease debt servicing costs it is a clear signal that debt has been overused — and largely for non-productive reasons. The desire to continue down the same path goes hand in hand with the desire to create inflation.

Rest assured that just as the amount of outstanding debt has spiraled uncontrollably higher, so too will inflation. The hubris of central bankers who somehow believe they will know the precise time to alter easy money policies in order to prevent a monetary disaster is only exceeded by the foolishness of Congressional oversight in granting that authority.

While current economic theories and policy actions invoke the name of John Maynard Keynes as a means of defense for such recklessness, we tend to think Lord Keynes would be appalled at what has transpired. In his words: “By a continuing process of inflation, government can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens.“

Follow the munKNEE – Your Key to Making Money!

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money